Gypsy Jazz Guitar: Django Reinhardt's Seminal Style

With its frenetic rhythms and wildly journeying solos, gypsy jazz guitar—or accurately jazz manouche guitar (pronounced: /ma.nuʃ/ or man-oosh)—conjures up visions of wild revelry and bacchanalia. I can turn these tunes on, close my eyes, and immerse myself in the imaginings of the legendary cultural caravans filled with bejeweled travelers who dance in cobbled streets late into the night.

This is a style that arose from an opportune blend of international cultures in post-WWI France and from the prowess and determination of one particularly skilled Roma guitarist, Mr. Jean “Django” Reinhardt.

Listening to the original Reinhardt hits, it’s pretty easy to imagine club-goers just absolutely getting DOWN to these bangers when they first appeared on the scene back in the 30s. It’s no wonder this springy, jivey genre still gets us rocking today, almost a whole century since it started making its way through the clubs of Paris.

Gypsy jazz guitar remains as interesting a style to learn about as it is to play, although its origins are about as complicated as its technique.

So, I’m gonna do my best to give a little historical context as well as an overview of what exactly makes up the admittedly complex jazz manouche guitar style—I can only hope I would do Django proud.

Origins of Gypsy Jazz Guitar

How France Liked to Dance

So, to get to the roots of gypsy jazz guitar, we need to head on back to Paris around the end of the 19th Century.

In the last few decades of the 1800s, Paris saw a huge cultural boom. Art, music, engineering, and technology all flourished.

This was the period known as the Belle Époque. It lasted just over four decades, from 1871 to 1914, and saw the construction of the Eiffel Tower, the near doubling of the Parisian population, and the rise of a popular type of dance club known as the Bal-musette.

Bal-musettes were festive bars and cafes that doubled as dance halls. These were spaces first opened by Parisian newcomers from the Auvergne region of France, who brought with them lively music centered around the bagpipe (a musette) and the hand-cranked hurdy-gurdy.

As people flocked from all corners of the world to the ever-exciting Paris, they melted into the city rhythm while adding their own regional touch of spice. In the case of Bal-musettes, Italian immigrants quickly adapted the bagpipe-driven genre to their own accordions and shook the scene up with their addition of exotic waltzes and polkas.

Eventually, the cafe/dance-hall hybrid Bal-musette split into three different types of clubs: those featuring Auvergnat musicians, those featuring Italian musicians, and a third type—ill-reputed hangouts for the lower elements of society (you know, the poors). So while the upper classes enjoyed the finer bal des familles and bal musette populaires, the less-affluent majority danced most of their nights away in the rough and rowdy bal de barrières.

The Belle Epoque ended when the First World War began, and for the next four years, entertainment took a back seat to the war effort. But it was during this time, right toward the tail end of WWI, when the seeds of a great musical movement would first be transplanted in France.

U.S. soldiers arriving to join the Allies in 1917 brought with them not only military aid but also a hot new style of American music known as jazz. It would still be some years before jazz became a staple in the French charts, but its introduction to the Old World left a lasting impression on many of the dance hall musicians of the time.

Enter Django

In the final year of WWI, a group of travelers—Romani people from the Manouche clan—settled on the outskirts of Paris. In their company was the 8-year-old Jean “Django” Reinhardt.

Django was born into music, with a mother who performed as a dancer and a father who worked as a violinist and guitarist (as well as a juggler and basket maker, depending on the season). Entertainment was the family trade, so it was only natural that Django, as well as his younger brother, Joseph, would take it up at an early age.

With the violin under his belt, Django was gifted a banjo-guitar a short while after his arrival in Paris. Starting around the age of 13, he began accompanying accordionists in some of the local bal de barrieres, helping keep the beat in several Parisian dance clubs.

Through both his club performances and busking with the younger Joseph Reinhardt, Django grew increasingly popular. His first recordings—a long set of lively polka-like musette tunes on which he played the banjo-guitar—earned him his first taste of international fame in 1928.

Having traveled to Paris to watch Django perform, English bandleader Jack Hylton (the “British King of Jazz”) offered the elder Reinhardt a place in his group, which Django accepted straightaway.

However, fate would play much differently for the promising young guitarist.

For, one night, returning to his caravan after a performance, Django tipped over a candle which rapidly set his wagon home ablaze. He was severely burned and subsequently hospitalized for a year and a half. His injuries were extensive, and the burns caused serious damage to his right leg and his left hand. The injury to his leg nearly resulted in amputation, and the third and fourth fingers of his fretting hand were rendered in a permanent downward hook.

This accident crippled Reinhardt, but it did not kill him, and that made all the difference. Django, as a prime example of human perseverance in the face of setback and tragedy, not only regained the ability to walk, but through his genius and determination, developed an entirely new guitar technique adapted to his fretting hand’s loss of mobility.

It wasn’t long after his recovery that Reinhardt was first introduced to jazz music, which is said to have had a profound and immediate impact on the guitarist. Inspired by the recordings of America’s jazz legends—Armstrong, Ellington, Lang, and Venuti—Django set his mind and soul to crafting his own signature jazz technique.

Gypsy jazz emerged much like a phoenix from the ashes; a novel and exciting style forged from the dance music of pre-war Paris, the revelrous and wandering Manouche energy of Reinhardt’s heritage, and the boundary-breaking jazz issuing from the States, rising from the ashes of Django’s fiery accident.

The Hot Club Quintette

Within no time, Django was back to performing. This brought him to be involved with the dance orchestra at the Hotel Claridge in the early 30s. It was here that the members of what would become the hottest jazz group in Europe first met: bandleader and bassist Louis Vola, guitarist Roger Chaput, and violinist Stéphane Grappelli. Accounts vary of when and where each respective member met one another. But it was here at the Hotel Claridge during backstage jams between sets that the four, with the addition of Django’s brother Joseph, decided to form the jazz quintet known as the Quintette du Hot Club de France.

Pushed by enthusiastic concert promoters, the group began recording in late 1934 and was basically an overnight success. Grappelli and Reinhardt were a synergistic duo unlike any that had quite been heard before, thrilling audiences with hits like “Dinah”, “Lady Be Good” and the ever-popular “Minor Swing”.

Their sound was quickly noticed by others and emulated both on the main scene and in the Romani settlements. Word was getting around that “Hot Club jazz” was the next big thing.

Although the supporting lineup changed, Reinhardt and Grappelli formed the constant powerhouse that propelled the Quintette du Hot Club de France for the next five years. Between 1934 and 1939, the Hot Club founders pumped out record after record while touring across Europe, as well as stepping in as session musicians for other acclaimed artists of the time. Their performances and recordings set the ball rolling on this hybrid new jazz form, setting the stage for decades’ more musicians to issue tunes based on exotic minors, rhythmically pumping strings, and wild improvisational techniques developed under the unique left-hand handicap of Django Reinhardt.

Defining Gypsy Jazz

Like most of the labels we use to describe music, the term “gypsy jazz” is a pretty broad umbrella, and not everyone agrees on what falls under it. Some even go so far as to say that gypsy jazz doesn’t exist at all—or at least is not sufficiently distinct to be classified apart from the more generic continental jazz that pervaded Europe in these same decades.

Our common name for this branch of music deserves some scrutiny itself, and we might do better to call the genre by a less Anglicized name in years going forward. The word gypsy has been used commonly enough as a pejorative, or downright slur for the Romani people that I like to suggest we all try to use the more appropriate jazz manouche when paying homage to this Django-associated style.

To monolingual ears, calling it jazz manouche may detract from the color and imagination we’ve attached to the name of the genre, but I think we can help it catch on. Manouche comes from the Romani word for people (manuś), and considering this genre’s multicultural origins, I’d say “the people’s jazz” is a much more honorary title in any case.

How Django Jammed- The Hot Club Sound and Style

Aside from Reinhardt’s absolute musical mastery—his melodic intuition, composition skills, energetic passion, and killer technique—it’s hard to say exactly what sets “gypsy jazz” apart from, well, jazz.

Django wasn’t aspiring to write Romani music with the Hot Club Quintette; he was just jamming to his new favorite American genre in the best way he knew how.

Truly, there’s no specific set of conditions music meets in order to be jazz manouche—in a sense, it’s more of an idea than a genre. But, if we average all the songs most often associated with the style and the genius behind it, there are some common traits we can say generally make up the gypsy jazz category.

La Pompe Up the Jams

Jazz Manouche was born in boisterous dance clubs, and as such it’s an energetic genre. Traditionally focused on string instruments and lacking percussion, it wasn’t uncommon in its early days for three guitars to drive the rhythm at once.

It’s what you might call a heavy-handed genre, with a persistent pulse that’s meant to be played loud and proud.

In fact, the most common gypsy jazz guitar rhythm is called, “The Pump”, or rather la pompe.

La pompe is far from the only groove that Django ever used, but it has become the rhythm technique most people associate with this style. Heavily emphasizing the 2 and 4 beat, la pompe drives hard and strong to make up for the genre’s lack of drums. Subtle upstrokes on the 1 and 3 keep the beat swinging as regular left-hand mutes create the signature percussive pump.

Progressions in jazz manouche are full of frequent chord changes and packed with 6/9, 9, and various 7 chords. The thumb is often used to fret bass notes, and non-stop barre chords are a given in any standard. Like with Reinhardt’s leads, chromatic progressions are not unusual. All told, rhythm guitarists are guaranteed to work as hard as anyone else in the group and serve an essential purpose in delivering the classic gypsy jazz vibe.

Taking the Lead

Django was one of the most accomplished guitar players to ever live, and there are literal books written about his guitar technique.

If you’re endeavoring to learn gypsy jazz guitar, there are a few things you should know:

- You’re going to be playing fast—like, really fast: Django’s solos often clock in at 300 bpm.

- Get ready to get fancy: Reinhardt was known for extensive embellishments in his leads.

- Arpeggios are your friend: you’ll be doing tons of sweep picking up and down the neck.

- No note is off-limits: the whole fretboard is yours to use in jazz manouche, and chromatic scales abound.

Reinhardt was truly a jazz guitar genius, and you’ll need years of dedication and practice to achieve an “authentic” gypsy jazz sound (if there even is one, but more on that a little later). From the position of the strumming hand to the special muting technique and two-finger runs of the fretting, there are many subtle characteristics of jazz manouche guitar technique that require careful study to get down correctly.

There are lots of great guides in all forms on gypsy jazz guitar technique, so you can really start learning right away. As with any new style, I think the best thing you can do to begin is to listen to the classics with the goal of understanding the music. Django’s jazz was intuitive, driven by love and passion for the art form, and this is evident in his recordings, so now’s a good time to turn on some Quintette du Hot Club and start to get the hang of what Reinhardt was all about.

A Note on “Gypsy Jazz Guitars”

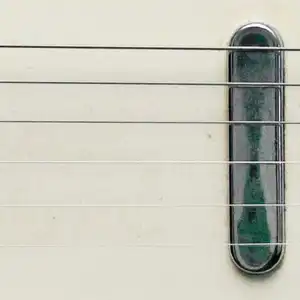

There’s a lot of hype surrounding the stand-out Selmer-Maccaferri acoustics. Commonly touted as “gypsy jazz guitars”, some guides recommend them as a necessity to mastering the genre.

I would like to counter by saying that you absolutely do not need a Selmer guitar to play jazz manouche. One might say that the more articulate guitar, the better for this style, but Selmer-Maccaferris are the gold standard only due to their association with Reinhardt, and that just because they were a popular guitar in France during the Hot Club’s hottest years. They were loud and responsive enough to cut through the crowd noise, but in no way are they necessary to learn Django’s technique. We would all be chasing this sound with a Telecaster if it occurred 20 years later.

You can read more on this and an extraordinary wealth of other Django-related information here.

The Right Tools for the Job

If the guitar is not as important for that Iconic sound and technique - what is?

The most responsible parties for Django's iconic sound (besides the great maestro himself) would be strings, picks, and picking position. Django had incredible right-hand technique. Jazz Manouche uses 'rest-stroke' based picking. Similar to the classical technique of the same name, you let the pick land on the next string, effectively picking 'through' it. To facilitate this picking motion, Django would rotate his arm, as if turning a doorknob, to deliver great force and speed onto the string whether strumming or picking. Described in the community as 'peaking at your cards', this upturned hand delivers a tremendous volume on it's descent. This technique is best implemented near the bridge, to get that bright and boisterous sound as your home base, and allowing so sul tasto picking near the neck to warm it up now and then.

Django used very light strings to get a thin and articulate sound, with as thick a pick as was possible in order to have exacting control over picks strings that thin.

The closest analogs in our Acoustic Guitar String catalog are our 10/50 Stringjoy 80/20 Brights, which feature a cuprozinc alloy that does a good job of simulating the less durable silk and steel formula Django would have played, but minus that silver that really wants to oxidize! Our Brights also feature a ball-end that enables their use on your average acoustics of today. We suggest 10/50 Stringjoy Naturals if you want something with more mids but still with that iconic slack and unresonant sound. Fair warning: We wouldn't consider this a typical acoustic sound, but neither was Djangos!

The other end of that agenda would be some of our thicker plectrums, from our 1.5mm Black Cherry picks or 1.14mm Grape picks in their tri-tip or jumbo jazz shapes to allow a lot of gravity to take over and attack.

You can read more on this and an extraordinary wealth of other Django-related information here.

The Legs and Legacy of Reinhardt’s Hot Jazz

Django lived a life of legend. Said to be magnetically charming, vibrant, and a generally great guy to be around, he became a multi-continental rockstar and imprinted himself firmly in the annals of music history purely by showcasing the wild and wonderful talent for which he held so much love. He died suddenly one night while walking home from yet another Parisian performance but had already kindled a fire that would continue to burn long after he was gone.

As a product of peace and conflict, poverty and prosperity, fairytale and tragedy, jazz manouche has proven itself to be a lasting cultural asset. Even after the horrors of the Second World War, it suffered only a couple decades of decline before coursing back into popularity in the 70s, thanks largely in part to the Roma musicians (such as Joseph Reinhardt) who so aptly kept it alive.

From the first days of the Hot Club Quintette, Django’s renown and rise to fame sparked interest in many who shared his cultural background, and the new jazz spread with ease. Members of Reinhardt’s family took up the technique, as did others in and outside of the Romani community, and soon there were regional variants worldwide.

Entire dissertations have been written about the significance of jazz manouche to the Romani people. Huge annual festivals pay tribute to Django the man and the music that he helped inspire. There have been films, songs, and even currency dedicated to Reinhardt, while walls of recordings stand in testament to the inspiration it holds for musicians across the globe.

Whatever we call it—gypsy jazz, jazz manouche, Hot-style, what have you—the impact of Django Reinhardt and the popularity of his particular flavor of jazz are maybe more pronounced now than ever before.

If Django’s tale of perseverance and absolute triumph in the face of tragedy has inspired you to likewise rise up against a great difficulty, I’m sure a worthy challenge awaits you in any one of the over 900 recordings Reinhardt left behind.

Other Posts you may like

Guitar Strings Order: How the Guitar is Tuned and Why

Best Acoustic Guitar Strings for Beginners

Two Handed Tapping: Our Top 8 Tappers of All Time

Which Guitar Strings Wear Your Fret Wire Down More?

What is Nashville Tuning? Its History, Best Guitar Strings & Uses

Guitar Scale Length Explained: String Tension & Playability

0 Responses

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *