The Nashville Number System Explained

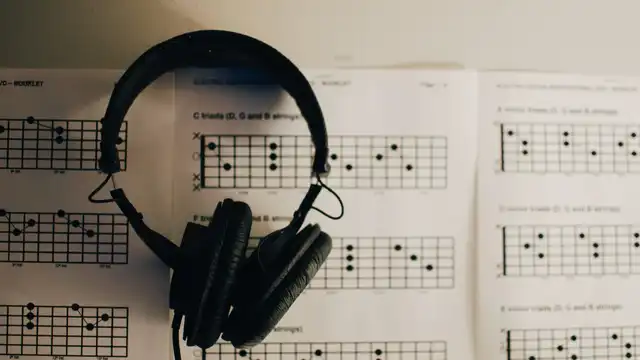

There are many different strategies and systems for understanding music theory, but none is more common than the Nashville number system (NNS). The NNS has become a standard for professional musicians in nearly every genre, and for good reason—it is an incredibly effective way to write and communicate chord progressions/charts, whether on paper or on-the-spot.

In this guide, we’re going to explain the Nashville number system and how it works so you can use it too. Thankfully, the NNS doesn’t require you to be a theory-wiz or virtuoso and only requires basic music theory. So let’s dive into the Nashville number system and see why it has become the accepted shorthand amongst working musicians.

What is the Nashville Number System and Why is it Useful?

Simply put, the Nashville number system is a shorter and quicker way to write and communicate song charts/chord progressions. Instead of G, C, and D, it’s 1, 4, and 5. At first, that doesn’t seem like much. What’s wrong with just saying the chords, like G, C, and D? But as things start to get more complicated, it quickly becomes essential.

Part of what makes the NNS so special is that it doesn’t change. When you write out a song using the NNS, it will be the same if you change keys. The 1 chord will still be the 1 chord, and the 5 chord will still be the 5 chord. So if your singer needs to change keys, you don’t have to rewrite the entire chart and are already ready to go.

One of the other things that makes it so useful is its ease of use. Because of the simple shorthand, it’s perfect for communicating changes during a song. You can easily hold up the corresponding number of fingers to let your bandmates know what chord is next. Trying to talk on-stage is a hassle, so being able to quickly communicate chord changes via fingers is essential for live performances, live-in-studio settings, and improvisation.

Understanding the Nashville Number System

So the Nashville number system is a shorthand way to write and communicate song charts/chord progressions, but how do you actually use it? Let’s take a closer look at how the NNS works so you’re ready to implement it on your own. Here are the five key components to understanding the Nashville number system.

1. Major Scale

First off, let’s start with a plain old major scale, as the NNS is built around it. We’ll use a C major scale since that’s the easiest one to work with. The C major scale is: C-D-E-F-G-A-B.

Each note of the major scale can then be built out into a chord. The easiest way to visualize this is on a piano. Start with a C major triad (C, E, and G). From there, you can play that exact same shape, but start on each of the notes of the major scales. If you do this, you’ll get each corresponding chord. The triads you’ll get are:

C (C–E–G)

Dm (D–F–A)

Em (E–G–B)

F (F–A–C)

G (G–B–D)

Am (A–C–E)

Bdim (B–D–F)

Now, take note of the pattern of the chords. Certain chords are major, while others are minor (plus one diminished chord). Knowing this pattern is crucial in using and applying the NNS. We’ll also attach a number to each triad based on the root. So C is 1, Dm is 2-, and so on. The pattern you get is:

1 Major

2- Minor

3- Minor

4 Major

5 Major

6- Minor

7° Diminished

An important thing to note here are the symbols used next to the numbers. A minus symbol (-) is used to designate a minor chord, and a degree symbol (°) is used to designate a diminished chord. This will become very important later on, so remember it.

With that in mind, let’s move onto the next part of the number system.

2. The Numbers

Okay, now it’s time for the numbers. Above, we broke down the pattern for triads made out of a major scale and attached a number to each chord. So now, we can use that knowledge and put it to use.

Let’s start with an example. I have a song in the key of C that uses the 1, 5, and 4 chords. Because we know the key is C, we know that the 1 chord is C, 5 is G, and 4 is F. But what about the quality of the chords? Are they major or minor?

Because of the pattern established above, each number in the number system has an implied tonality. 1 is major, 2- is minor, 3 is minor, and so on. So using that knowledge, we also know that the 1, 5, and 4 chords are implied to be major.

As you can see, the NNS allows you to quickly communicate a lot of information with just numbers. Instead of saying each chord and its tonality, you can simply use the numbers. At first, this may seem even more complicated than just saying the chords. However, it quickly becomes second nature once you understand it. It also becomes much more useful once you start changing keys.

3. Minor Keys and Changing Keys

Now let’s take our example song from before and pretend we’re performing it with a singer who needs a different key. Instead of C, they want to sing it in E and we have to transpose the chords.

Because of the NNS, we can use the exact same chart. The numbers/changes are still the same—1, 5, and 4. All we need to know is the notes of the E major scale, and we can quickly work out all of the chords.

In the key of E major, 1 would be E, 5 would be B, and 4 would be A. And since we know from the pattern earlier that 1, 5, and 4 are all major, we know E, B, and A are all major chords. With a thorough understanding of the number system, you can figure all of this out in mere seconds.

But what about the elephant in the room—minor keys? Everything has been based on major scales and keys so far, so how do minor keys fit into the equation? Thankfully, that’s pretty simple too.

For minor keys, you just use the relative major. Each major and minor key has a relative key that consists of all the same notes (and triads), but starting at a different point. C major’s relative minor is A minor and vice versa.

So, let’s say you’re playing a jam in Am with the chords Am and F. Since Am’s relative major is C, you use C as the base for the number system. In C, Am is the 6- chord (remember, minor chords are designated with a minus sign) and F is the 4 chord. Your Am to F progression would be a 6- and 4 progression with the number system.

4. Riffs, Rhythms, and Notes

Alright, so what about chords that don't fit into the predetermined pattern, like chords that are borrowed from another key or chords with embellishments like a minor 9 or sharp 7?

Like the minus and degree symbols used to indicate minor and diminished chords, there are other shorthands used to communicate other information. For example, adding a 7 above a chord (say a 17) indicates that it’s a 7th chord. A minor 11th chord would have (-11) next to the chord.

There are other shorthands as well, such as a diamond above chord indicating it should be played as a whole note left to ring out a full bar. These shorthands can vary from person to person or group to group. As long as everyone knows what the shorthand means, you can include as much information as necessary.

NNS charts also often include rhythm figures/riffs, as those can’t necessarily be communicated solely through numbers. For example, let’s say you're supposed to play an Am chord, but it’s supposed to be played with a very specific rhythm. You or whoever writes the chart can just write in the rhythmic figure somewhere in the chart and indicate when it should be played. So you might have something on the chart that looks like this:

Intro riff: ♩♫♩♩

Again, just keep in mind that a lot of the shorthand is unofficial and can vary. If you see something you aren’t sure of, just ask whoever wrote it (or someone else who might know).

5. Beat Value

Finally, let’s talk about rhythm and beat value. Since the Nashville number system doesn’t use staff paper, you need another way to communicate rhythms (addressed above) and beat values. Again though, it’s all pretty simple.

With the NNS, it’s assumed that one number (say a 1) equals one measure or bar. In 4/4 time, that’s four beats. In 3/4 time, that’s three beats. So what do you do when you have a measure with more than one chord, like two chords for example?

All you have to do is underline the chords, and it implies that all of those chords take place within the measure. So if you have a measure where you want to go from a 2 to a 5, you would just write it as 2- 5. But what about if you have more than two chords, like if you have a passing chord?

Then, you can underline the chords and designate the length underneath with a tick mark (each tick equals one beat). So if you want to go 1, 2-, 5 but want the 1 to be two beats, you could write it like 1II 2-I 5I.

Start Writing Your Own Charts

The Nashville number system is used by professional musicians on stages and in studios every single day. It is an incredibly useful shorthand for writing song charts and communicating with fellow musicians. It’s something that everyone should be familiar with, regardless of what instrument they play.

With this guide, you should now be able to utilize the Nashville number system and more efficiently communicate with your fellow musicians. So get your guitar, some paper, and a pen, and get to work taking advantage of what the Nashville number system has to offer.

Other Posts you may like

Guitar Strings Order: How the Guitar is Tuned and Why

Two Handed Tapping: Our Top 8 Tappers of All Time

Which Guitar Strings Wear Your Fret Wire Down More?

What is Nashville Tuning? Its History, Best Guitar Strings & Uses

Guitar Scale Length Explained: String Tension & Playability

What Guitar Strings I Used To Play...

0 Responses

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *