Guitar Fretboard Woods: The Ultimate Guide

An element of guitar specs that is often overlooked is your fretboard (sometimes also called a fingerboard)—specifically, what it’s made of. There are almost innumerable options for fretboard woods in this day and age, ranging from the traditional wood of African ebony to materials that aren't wood at all, such as carbon-fiber composites first engineered for the aerospace industry.

I’m here to give you a rundown of these multivarious choices and to lend some insight into how they might affect your sound and performance.

Why Do Fretboard Woods Matter?

There’s a huge debate in the guitar community over whether or not fretboard woods have any significant impact on a guitar’s tone.

Some players swear they can clearly hear the difference between rosewood and ebony and assert that the contrast can make or break your tone. This school of thought takes into consideration things like how fingerboard density affects sustain, how porosity affects response and articulation, and how distinct wood grains change the frequency balance of an axe.

Other players couldn’t care less. For some, a fretboard’s a fretboard whether it’s made from AAA-grade silverleaf maple or some unbranded composite paper. To these guitarists, I say, “more power to you.”

I’m of the opinion that there is at least some degree of tonal difference from medium to medium, and I stand pretty firmly behind the idea that there’s a noticeable change in playing feel among the various types.

In the end, I guess it all comes down to personal preference (or lack thereof). Some of us are wood purists, desiring nothing but the time-honored all-wood builds of traditional guitars. I lean a little more toward this camp for reasons I can’t fully articulate, though I really find no fault in synthetic fingerboards.

Personally, I think that you know what’s best for your personal playing style and desired tone, and if the fretboard wood is something you don’t care to give much mind to, I don’t see a problem with it.

Ultimately, fretboard woods need to be hard enough to withstand the scratching friction of a guitar’s strings and durable enough to not crack under the compression caused by the tension of the strings. For centuries, luthiers have done a rather excellent job of producing fingerboards with these standards. In our current search for new materials to meet these requirements, we look back upon traditional builds to guide our builds as we further the development and evolution of the guitar so widely loved.

Fretboards Through the Ages

It might be a tad surprising to find out we have hardly deviated from fretboard designs for half a millennium. Though there have always been those looking to experiment and break from the norm, the overwhelming majority of guitars and guitar ancestors have been made with very similar materials.

We’ll take a little tour through time here and look at the development of our fretboard wood choices since guitars first started taking shape all the way up to today.

Proto-Guitar Fingerboards

Before the six-stringer we’re all familiar with today was the 15th-century Spanish vihuela. From these and their lute cousins came an array of guitar-like predecessors, ultimately leading up to the contemporary guitars of today.

These were among some of the first instruments with dedicated fingerboards, and the earliest on record with specified specs is the vihuela grande de piezas, described in the 1502 Sevillan manuscript Examen de Violeros. In this set of regulations, quality vihuelas were deemed to have cedar bodies and necks of either walnut or ebony.

So it is that we see the beginnings of that most revered of the fretboard woods, the dark and dense African ebony. This would set the fingerboard standard for centuries to come, establishing a tradition that has come nowhere near to dying out.

One hundred years after the publishing of these vihuela guidelines, we come across a rosewood fretboard in a five-course guitar crafted by the Italian Christopher Cocko. This is the earliest introduction of the famed rosewood I can find, though it would be still more than two centuries before rosewood became established as a fretboard wood of choice.

In the developmental years of the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, luthiers employed a fantastic assortment of materials into their instruments, ranging from walnut, ebony, and rosewood to the more exotic mediums of bone, ivory, mother of pearl, and tortoiseshell. Even up to the 1800s, these now totally non-standard materials were being widely used in guitars—the Martin “Italian-style” guitar of 1836 had a fretboard of pure ivory! But throughout this time, ebony was exceedingly the dominant wood of the trade.

The Rise of Rosewood Fretboards

It wasn’t until the middle of the 19th century with the innovations of Antonio de Torres that we start to see more and more guitars made with rosewood fretboards. Torres’ designs were so revolutionary that most luthiers wanted to follow them to the T, so in the 1850s and onward there was a huge uptick in the number of rosewood-fretboard guitars.

By this time, the more lustrous (not to mention expensive) pearl and ivory fretboards were falling by the wayside. Guitars were becoming less a conversation piece for lords and dukes and more an instrument for the common layfolk. As such, the tried and true woods—namely ebony and rosewood—became the go-to materials for fingerboards that they would remain until modern-day.

Rosewood and ebony have remained the primary fretboard woods for the bulk of the guitar’s history. There was the occasional guitar with walnut and the “electric frying pan” aluminum build from Rickenbacker, but no serious fretboard contenders appeared until 1950 with the introduction of the Fender electric.

Maple Fretboards and More

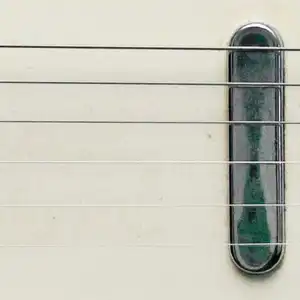

To keep manufacturing and repairs simple, as well as to add strength to the overall design, Fender started their guitar lineup with a one-piece maple neck. Renouncing the usual addition of a separate fingerboard, Fender’s first guitars had the frets embedded directly into the neck wood. Their guitars were a hit, and maple became one of the new leaders in fretboard woods.

So it was that ebony, rosewood, and maple were the primary choices of fretboard woods for the greater part of the 20th century. If you bought a guitar, chances were that it would be outfitted with one of these three, as their density, strength, hardness, and pore shape made them ideal to withstand the rigors of guitar playing.

Here we come to the infamous CITES treaty, originally adopted in 1975 and having far-reaching effects today in all industries which rely on “exotic” woods. In a nutshell, CITES is an international agreement among 183 countries that aims to protect at-risk and endangered plant and animal species by restricting their import and export. This is all well and good and didn’t really impact the musical instrument industry until relatively recently.

In 2017, all types of rosewood were added to the CITES protections. A large demand for rosewood furniture in China drove up the rosewood logging industry, which ultimately led to a humanitarian crisis in parts of Africa involving a rise in violent sourcing practices and an environmental plight in Brazil tied to deforestation. To curb this, CITES heavily restricted the flow of all species of rosewood to and from the affected areas. This meant that the export of raw rosewood (logs) as well as the import of items containing rosewood were dependent upon receiving numerous, hard-to-attain permits.

Consequently, instrument manufacturers began looking for rosewood alternatives. Several suitable replacements have been identified and are currently in rather wide use over a broad selection of brands, such as pau ferro, Indian laurel, and ovangkol, all of which have a similar hardness and sonic response as rosewood.

The unintended consequence of the CITES rosewood regulations included the seizure of instruments from traveling musicians. As a result, there was a great pushback from vocal opponents of these restrictions. In 2019, CITES ceded—to a degree—some control of instrument-related rosewood, easing the travel restrictions that had been resulting in the seizure of traveling artists’ prized instruments.

However, tonewood troubles didn’t end there. Ebony has now been overharvested to the point that it is becoming a true scarcity. While some companies have turned to sustainably harvested ebony, others have looked for altogether different alternatives. Some have chosen to substitute with woods that are more abundant and able to be harvested with less environmental risk, such as blackwood and wenge. Furthermore, we are now seeing the rise of synthetic fingerboards made of materials like Micarta and Richlite. These man-made substances offer the same strength and hardness of ebony while being much more sustainable.

The future of fretboard tonewoods remains unclear, but it is unlikely that ebony and rosewood will continue to be the prime choice for much longer. As the demand for guitars increases, so does the need for manufacturers to find alternative materials that can be sourced without great environmental detriment. These traditional woods did a splendid job of elevating the guitar from a pure accompaniment piece to its current prominent position, but now it may be time for them to take a backseat while we explore the tonal opportunities afforded us by other sorts of woods and wares.

Choosing the Right Fretboard Woods for You

While I may not think that fretboard woods have a make-it or break-it kind of impact on your guitar’s sound, it would be negligent of me to not devote a section to sharing the common conceptions of their tonal differences. To that end, let’s go over a brief overview of the most popular fretboard woods and their professed sonic characteristics:

The Big Three Fretboard Woods

Ebony

Considered the supreme tonewood for fingerboards due to its solidity, resiliency, and firmness, ebony was the primary fretboard wood in use from the 15th century till very recently.

It is smooth and oily even when unfinished, giving it a fast playing feel and great responsiveness.

Favoring the fundamental, ebony lends a snappy crack to your tone and a solid amount of sustain.

Rosewood

Known to even out a treble-heavy body tone, rosewood has been a favorite for nearly two centuries now.

It is described as soft under the fingers despite being a hardwearing wood that stands up to the strain of frequent performance.

It is a warm, tempering wood that can add a sweet amount of overtones to an otherwise choppy voice.

Maple

Fender guitars really brought maple into the venerated territory it stands today.

Popular for its biting response and sharp attack, maple dashes a guitar with high-end sparkle that helps in cutting through muddy mixes.

With tight pores and little natural oil, many describe the playability of maple as quick and slick.

Up and Comers

Indian Laurel

Laurel is fast becoming the replacement to rosewood on many Fender guitars.

It is a moderately hard wood with a generally straight grain that makes for a smooth, balanced response and a delicate playing feel.

Ovangkol

As a tropical relative of rosewood, ovangkol shares many of the same tonal traits with its more-renowned cousin.

It is a wood of medium density with an interlocking grain that makes it great for fretboards.

Sonically, it is thought to fall between the warmth of rosewood and the sparkle of maple, with a smooth attack and adequate sustain.

Padauk

Though it may be more prone to weather-induced warping than harder wood varieties, padauk is currently considered one of the more viable candidates to replace rosewood in the coming years.

It provides a punchy tone with a relatively fast note decay, but this is compensated by its richness of overtones and aural depth.

Pau Ferro

Pau ferro is very similar to rosewood. It is an oily, reddish wood that is smooth to the touch and low on maintenance.

With a denser grain than rosewood, it delivers much of the same harmonic qualities while offering a faster attack and added treble shimmer.

Walnut

Though not exactly a newcomer to the tonewood game, walnut never reached the same levels of popularity as the main three.

It has a resilience on par with rosewood but a differing grain pattern that gives its tone a slightly crisper character.

Synthetic Fretboards

Richlite

Richlite is a paper-based carbon fiber composite originally developed for aerospace machine tooling. Since then it has found a huge array of applications in the industrial and furniture industries.

It’s now become known as a reliable, sturdy substitute for ebony, conveying a highly similar playing feel and sonic response.

Micarta

Micarta is coming to be known as Martin’s answer to the ebony shortage. It is quite similar to Richlite in that it is a carbon fiber composite, but it is often reinforced with fiberglass.

Don’t worry, it’s not sharp! Micarta’s playability and tonal attributes are so much like ebony, many players have a hard time telling the two apart.

Rocklite

An up and comer in the up and comers, Rocklite is a non-particulate-based composite being praised for its resemblance to “the real deal”.

Though it seems they’re closing guarding their process, I can tell you that it’s a blend of eucalyptus and tulipwood with a slightly lower density than ebony.

It is offered in both a rosewood and an ebony form, with variable grains that look and feel very close to the true tonewoods.

Wrapping Up

While it’s awesome we have more tonewood choices for customizing our guitars than ever before, it’s a sad fact that this is due to poor stewardship of our natural resources.

Maybe, in time, the ebony and rosewood forests will have a chance to regenerate, and perhaps then we will be able to return to these time-honored tonewoods with a more eco-friendly approach.

Until then, let’s break free from the thought that all other woods can’t compete, unshackle ourselves from the limiting vices of tradition, and bravely explore the musical landscape armed with axes made of strange, new woods.

After all, one could argue that it’s the player who makes the guitar sound good and not the other way around.

Author’s Note: If you found the historical information in this article particularly interesting, I would definitely recommend digging into this book, it’s where I pulled most of the information for this article from.

Other Posts you may like

Guitar Strings Order: How the Guitar is Tuned and Why

Two Handed Tapping: Our Top 8 Tappers of All Time

Which Guitar Strings Wear Your Fret Wire Down More?

What is Nashville Tuning? Its History, Best Guitar Strings & Uses

Guitar Scale Length Explained: String Tension & Playability

What Guitar Strings I Used To Play...

0 Responses

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *